As an instructor in a fully online program, I often use group work as a means to increase engagement and facilitate a connection in the online classroom. In some classes, I ask students to work in groups on individual assignments, but for the purpose of giving and receiving feedback on their respective projects. For example, in a course on Nutrition Education Methods, students work to develop individual lessons that they ultimately deliver at the end of the term. In this case, peer feedback is used to strengthen their work. In other classes, I ask students to work together in groups where they all contribute to a larger, shared project that they submit at the end of the term. In a course on Health Communication, for example, students work collaboratively to develop and implement a social marketing campaign that addresses a health-related issue of their choosing.

In course evaluations, the group assignments established for giving and receiving peer feedback are generally well-received and students note their appreciation for their groups’ remarks. In the second example, student evaluations about their experience are often mixed. Some report a positive group experience, while others are disappointed with the final outcome.

The ability to work collaboratively with a team is a skill that serves students well beyond their college years. A recent article on LinkedIn Learning (Pace, 2020) outlines the “soft” skills that companies are seeking in prospective employees in 2020. These skills include creativity, persuasion, collaboration, adaptability, and emotional intelligence – all skills that “demonstrate how we work with others and bring new ideas to the table” (Pace, 2020, para. 2). As an instructor, I see the larger benefits of collaborative learning, but recognize how these assignments translate in the online classroom isn’t always successful.

In this review of the literature, my aim is to share the results of my research on collaborative learning and its applications in the online environment in higher education, as well as the circumstances that make collaborative learning a positive experience for students and teachers alike.

The word collaboration “suggests a way of dealing with people which respects and highlights individual group members’ abilities and contributions. There is a sharing of authority and acceptance of responsibility among group members for the groups’ actions” (Laal & Ghodsi, 2012, p. 486). Collaborative learning requires that learners work together to make connections and uncover new ways of understanding concepts (Laal & Laal, 2012 as cited by Falcione et al., 2019). Falcione et al. (2019) add to this definition by explaining that collaborative learning is a way for students to intertwine their independent work in order to achieve a shared goal. The results of these efforts are a “product or a learning experience that is more than the summation of individual contributions” (Falcione et al., 2019, p. 1).

The foundation of collaborative learning is the idea that learning with others is better than learning alone (Nokes-Malach et al., 2015). In fact, the primary goal of team-centered, collaborative environments is to apply the unique backgrounds and skills that individuals bring to a group and accomplish something together that they may otherwise be unable to accomplish individually (Roberts, 2004).

Online learning naturally lends itself to student-centered instructional strategies and assessments, and collaborative learning most certainly fits this category (Muller et al., 2019). Given the physical distance that separates online students, collaborative learning efforts may also help students connect in an effort to dissolve any feelings of isolation they may be experiencing (Writers, 2018).

Harasim (2012) as cited by Bates (2015), offers the following definition of Online Collaborative Learning (OCL):

Online collaborative learning theory provides a model of learning in which students are encouraged and supported to work together to create knowledge: to invent, to explore ways to innovate, and, by so doing, to seek the conceptual knowledge needed to solve problems rather than recite what they think is the right answer (Harasim, 2012 as cited by Bates, 2015, para 1).

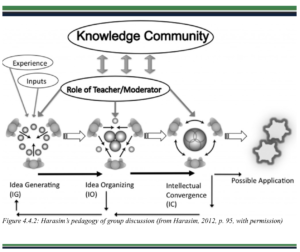

The image shown below depicts the core principles of Online Collaborative Learning and how these principles are operationalized through online discussions. Discussion forums often serve as the backbone for learning in online environments. Bates (2015) argues that online discussion forums are not meant to supplement course content (typically delivered through lectures and textbooks), but should be the central means for content delivery. Here, students identify readings and resources to support the discussion as opposed to allowing the readings and resources to be the driver. It is through this discourse that students are able to generate and organize ideas and ultimately achieve “intellectual convergence” by synthesizing the ideas presented (Bates, 2015). Because the discussion happens asynchronously, students have time to ruminate over the ideas presented and respond in a more thoughtful manner (Roberts, 2004).

Another important element of the Online Collaborative Learning model depicted above is the role of the teacher. Here, the teacher serves as a facilitator of the discussion in an effort to move students through the process of generating, organizing, and synthesizing ideas (Bates, 2015). The concept of “teacher” as “facilitator” is a hallmark of student-centered, online learning.

Collaborative learning is sometimes used interchangeably with the term “cooperative learning” (Writers, 2018). Balkcom (1992) defines cooperative learning as an instructional strategy that uses groups made up of diverse learners. Groups are engaged in a variety of activities to enhance their understanding of lesson concepts, and members have a shared responsibility to help one another learn and grow. A key component of cooperative learning is positive interdependence (What is Cooperative Learning, n.d.). Positive interdependence is established when students perceive that the contribution of each group member is essential to the success of the group. Scager et al. (2016) found positive interdependence to be a critical factor in successful collaboration.

While the two concepts share many of the same characteristics, Falcione et al. (2019), argues that cooperative learning is, in fact, different from collaborative learning. The primary factor that differentiates collaborative learning from cooperative learning is the independent work that group members do in order to contribute to the task at hand. This work is done at different times and is often developed alone. However, the individual’s work is later combined with the work of other group members in order to synthesize ideas.

The following video expands on this idea and identifies additional factors that differentiate collaborative learning from cooperative learning:

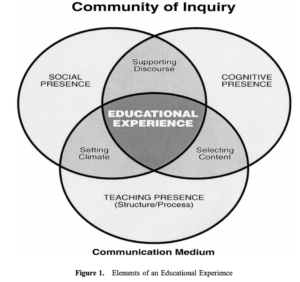

Another related concept evident in the literature is a Community of Inquiry (CoI). In the image below, Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2000) depict the CoI framework that they argue is integral to the online learning experience in higher education.

(Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000, p. 88)

Here, the educational experience is at the center of the CoI model, and learning takes place through the interaction of three vital components: social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence. Social presence represents the idea that individuals within the community are able to interject elements of their personality into the group so that they are seen as “real people” (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000, p. 89). Cognitive presence is deemed the most important of the three and refers to the ability of learners to “construct meaning through sustained communication” (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000, p. 89). The authors argue that cognitive presence is critical to developing higher-order thinking skills (which is necessary in postsecondary education). Finally, teaching presence is defined by two key functions: 1) course design and 2) facilitation. Essentially, the goal of teaching presence is to facilitate cognitive presence and social presence within the community (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000). Bates (2015) concludes that CoI and OCL are more “complementary rather than competing” (section 4.4.3) ideas and are, therefore, not mutually exclusive models for learning.

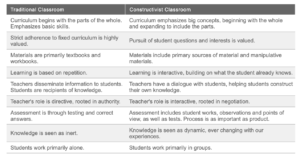

Online collaborative learning may be classified as a constructivist approach to learning (Bates, 2015). Constructivism is a theory that posits that learners actively construct knowledge as opposed to passively receiving it. This knowledge is further developed through life experiences allowing learners to develop mental models as a way to make sense of new information (Constructivism, n.d.). The table below outlines the differences between traditional learning and constructivist learning:

In the traditional classroom setting, collaborative learning can take on many forms. Problem-based learning, jigsaw activities, think-pair-share, and peer review are just a few common examples (Nokes-Malach et al., 2015). These strategies are defined in more detail below:

Problem-based learning: In this strategy, students work in groups to collaboratively solve a larger problem. The group work takes place over an extended period of time and often requires some deliverable at the end of the project (Active and Collaborative Learning | University of Maryland—Teaching and Learning Transformation Center, n.d.).

Jigsaw: This strategy takes a problem or task and divides it into smaller components. Each component is assigned to a group in order to gain a deeper understanding of the topic, who ultimately reports out in an effort to contribute their understanding as a piece of the larger puzzle (Active and Collaborative Learning | University of Maryland—Teaching and Learning Transformation Center, n.d.).

Think-pair-share: This strategy starts by dividing students into pairs. The instructor then provides students with a discussion prompt or question to consider. Individual learners reflect on the problem independently before sharing their thoughts or ideas with a peer. Once both students have had a chance to discuss, they may share a summary of their discussion with the rest of the group (Active and Collaborative Learning | University of Maryland—Teaching and Learning Transformation Center, n.d.).

Peer review: This strategy allows students to review one another’s work and provide positive and constructive feedback to facilitate improvement. The strategy teaches students as writers to receive, evaluate, and choose whether or not to incorporate the feedback into their work. As editors, it teaches students to analyze and clearly communicate feedback with their peers. As an instructor, it is critical to provide guidance and structure to best facilitate the process (Active and Collaborative Learning | University of Maryland—Teaching and Learning Transformation Center, n.d.).

All of these strategies can be adapted for the online learning environment, however, online collaboration tools, i.e. Zoom, Google Docs, Slack, or Trello, are often used to facilitate the transition (Writers, 2018). Tarun (2019) defines online collaboration tools as “web-based tools that allow individuals to do things together online like messaging, file sharing, and assessment” (p. 276). Integrating technology tools like these in the classroom fosters “authentic and meaningful learning experiences” (Boundless, 2015, sec 2) and also supports differentiated learning efforts (Boundless, 2015).

A basic search online for “online collaboration tools for education” yielded a variety of sites ranking the top-rated tools for digital collaboration (EDsmart, 2015; TeachThought, 2019). In the 2019 article, the tools ranked covered broad categories like tools for communication, project management, peer review, and game-based learning. Listed below are some examples that the authors highlighted in this post:

Diigo: Diigo is a social bookmarking tool that allows learners to collect, annotate, organize, and share online resources.

Flipgrid: Flipgrid is a tool that allows learners to create and share short videos and can be used for reflections, discussions, or short presentations. Additionally, peers can respond to posts in video form. The “grade book” feature within the tool allows instructors to track and monitor participation.

VideoAnt: VideoAnt is a tool that allows students and teachers to annotate YouTube videos. Here, students can ask questions or add critiques at various spots throughout the video.

Padlet: Padlet is a multimodal group collaboration tool. Here, students can collect videos, articles, or images and post them to a virtual corkboard. Students can also comment on posts in a threaded discussion format.

Appavoo, Sukon, Gokhool, and Gooria (2019) add that tools like WhatsApp, Skype, and Moodle are popular tools for online collaborative learning in higher education. These tools offer learners a way to discuss and share ideas and gain instant feedback. Furthermore, some students report that they prefer to learn on tools like these as they feel more open to discussing any academic-related issues they may be experiencing (Preston, Phillips, Gosper, McNeil, Woo, and Green, 2010, as cited by Appavoo et al., 2019).

Scager et al. (2016) note that there are decades of literature that demonstrate the positive effects of collaborative learning on academic success. In one such article, Laal and Ghodsi (2012) compiled and categorized the benefits of collaborative learning found in the literature between 1964-2010. The noted benefits were divided into four overarching categories to include social, psychological, academic, and assessment.

Social: Collaborative learning creates a support system for students as they work through challenges together. The group work also facilitates learning communities while improving student’s understanding of diverse viewpoints and strengthening cooperation.

Psychological: Learner-centered instruction improves self-confidence in the learner and working on problems together can help lessen feelings of anxiety for students. Affectively, collaborative learning efforts may lead to more “positive attitudes towards teachers”.

Academic: Collaborative learning creates a student-centered approach to learning, fosters higher-order thinking and facilitates problem-solving skills.

Assessment: Collaborative learning efforts use a multitude of assessment techniques.

Falcione et al. (2019) add that collaborative learning leads to a mastery of course content and the cultivation of interpersonal skills that benefit the student outside of the classroom environment.

In collaborative learning, the metacognitive ability of participants is improved due to the absence of a professor’s help throughout the process; learners must turn to each other, or outside sources, to overcome barriers, encouraging recognition of their own misunderstandings. (Davidson & Major, 2014 as cited by Falcione et al, 2019).

Benefits Specific to Online Collaborative Learning

Roberts (2004) describes additional benefits specific to collaborative learning in the online environment. Examples include:

While there are many documented benefits of collaborative learning, this strategy also comes with its fair share of challenges. One such challenge includes the “cognitive costs of coordinating and collaborating with others” (Nokes-Malach et al., 2015, p. 647). In other words, if an individual member can solve the problem independently, then they are not likely to benefit from collaborative efforts and may even perform worse as a result of trying to coordinate many varied ideas (Nokes-Malach et al, 2015 as cited by Nokes-Malach et al., 2012). This notion also applies to less complex activities where little is gained from group collaboration. Group members benefit when the task is complex, i.e. “high cognitive load”, and parts can be distributed among the group.

Other potential challenges described by Nokes-Malach et al. (2015) include “retrieval strategy disruption” and “production blocking”. The former concept occurs when one person loses their train of thought because they are paying attention to other group members, while the latter refers to the practice of allowing others to finish speaking before attempting to speak. This example can lead to “missed retrieval opportunities”.

A third example includes “social loafing” which describes the phenomenon where one group member may not contribute at the same level because they believe other group members may help “pick up the slack”.

A fourth, and final challenge is of collaborative learning is “fear of evaluation”. Here, students may avoid sharing ideas out of fear of judgment from their group members (Nokes-Malach et al., 2015).

Johnson and Johnson (2009, as cited by Nokes-Malach et al., 2015) propose that the latter two examples may occur when there is a lack of individual accountability or positive interdependence among group members as described earlier in this review.

It’s important to note that there are also drawbacks related more specifically to online collaborative learning efforts. One such drawback involves some of the online collaboration tools used. Tarun (2019) discusses the inadequacies of such tools to include a lack of features that may improve usability as well as the inability to customize some tools to meet classroom, instructor, or school needs.

Appavoo et al. (2019) add that collaborative learning efforts in online courses can be difficult to coordinate for learners, as some are also balancing professional and family-related commitments.

In order to overcome some of the common challenges of collaborative learning and maximize benefits, it is important to adhere to the recommendations that have emerged from the research on collaborative learning efforts (Scager et al., 2016).

The first factor that instructors should keep in mind when implementing collaborative learning efforts is to use a small group size (Scager et al., 2016). Three to five students per group is recommended to maximize efficacy (Cooperative learning classroom.research, n.d.).

Another factor to consider is group composition. Groups comprised of members with diverse perspectives have been shown to increase learning in group work (Kozhevnikov et al., 2014). It is interesting to note that mixed ability groups tend to benefit lower ability students and may not benefit higher ability students (Webb et al, 2002). What may be even more important when it comes to learning, however, is equal participation among group members regardless of “ability”. When all students participate equally, they are more likely to fully utilize each member’s unique skillsets and contributions (Woolley et al., 2015).

A third factor to consider is the nature of the task itself. For collaborative learning efforts to be most successful, tasks should be both complex and appropriate for the topic at hand. The task should also allow students to create unique work with autonomy and self-regulation (Scager et al., 2016), but within a structure or framework to guide collaborative learning efforts (Appavoo et al., 2019).

Last, but not least, for collaboration to be successful, social interaction is imperative (Volet et al., 2009). The process of discussing, debating, and explaining ideas to one another, as well as building off of others’ ideas helps to facilitate metacognition (Scager et al., 2016).

While the concept of collaborative learning certainly isn’t new, collaborative learning in a digital environment is for many teachers and students. With the advances in technology as well as the increase in quantity and quality of digital tools available, there is great potential for the future of online learning. To get to that point, however, it will be important to address some of the gaps in the existing literature.

Research efforts for this review uncovered fewer articles related specifically to online collaborative learning when compared to collaborative learning in the traditional classroom setting. Chang and Hannafin (2015) add that it will be important to consider the unique traits of adult-learners and the impact that online collaboration tools may have on learning for this group.

Tarun (2019) notes that research on educational technology tools most often includes tests of quality, to include “functionality and usability”, but fail to evaluate the effects of integration into the online classroom. In future research, it will be important to consider if and how the technology tools used for collaboration are actually accomplishing what educators believe they are accomplishing.

Active and Collaborative Learning | University of Maryland—Teaching and Learning Transformation Center. (n.d.). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from https://tltc.umd.edu/active-and-collaborative-learning

Bates, A. W. (Tony). (2015). 4.4 Online collaborative learning. In Teaching in a Digital Age. Tony Bates Associates Ltd. https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/chapter/6-5-online-collaborative-learning/

Boundless (2015, July 21). Advantages of using technology in the classroom. Boundless Education. Retrieved from http://oer2go.org/mods/en-boundless/www.boundless.com/education/textbooks/boundless-education- textbook/technology-in-the-classroom-6/edtech-25/advantages-of-using-technology-in-the-classroom-77- 13007/index.html

Chang, Eunice & Hannafin, M. J. (2015). The uses (and misuses) of collaborative distance education technologies: Implications for the debate on transience in technology. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16(2), 77–92.

Constructivism. (n.d.). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from http://www.buffalo.edu/ubcei/enhance/learning/constructivism.html

Cooperative learning classroom.research. (n.d.). Retrieved April 4, 2020, from http://alumni.media.mit.edu/~andyd/mindset/design/clc_rsch.html

EDsmart. (2015, December 29). 50 free online collaboration tools for educators. https://www.edsmart.org/50-free-online-collaboration-tools-for-educators/

Falcione, S., Campbell, E., McCollum, B., Chamberlain, J., Macias, M., Morsch, L., & Pinder, C. (2019). Emergence of different perspectives of success in collaborative learning. Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1227390

Kozhevnikov, M., Evans, C., & Kosslyn, S. M. (2014). Cognitive style as environmentally sensitive individual differences in cognition: A modern synthesis and applications in education, business, and management. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614525555

Laal, M., & Ghodsi, S. M. (2012). Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 486–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.091

Muller, K., Gradel, K., Forte, M., McCabe, R., Pickett, A. M., Piorkowski, R., Scalzo, K., & Sullivan, R. (n.d.). Assessing Student Learning in the Online Modality. 32.

Nokes-Malach, T. J., Richey, J. E., & Gadgil, S. (2015). When is it better to learn together? Insights from research on collaborative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 27(4), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9312-8

Roberts, T. S. (2004). Online Collaborative Learning: Theory and Practice. Idea Group Inc (IGI).

Scager, K., Boonstra, J., Peeters, T., Vulperhorst, J., & Wiegant, F. (2016). Collaborative learning in higher education: Evoking positive interdependence. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-07-0219

Tarun, I. M. (2019). The Effectiveness of a Customized Online Collaboration Tool for Teaching and Learning. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 18, 275–292.